When I was a wee boy growing up in the 1950’s and early 60’s it wasn’t that long after the Second World War.

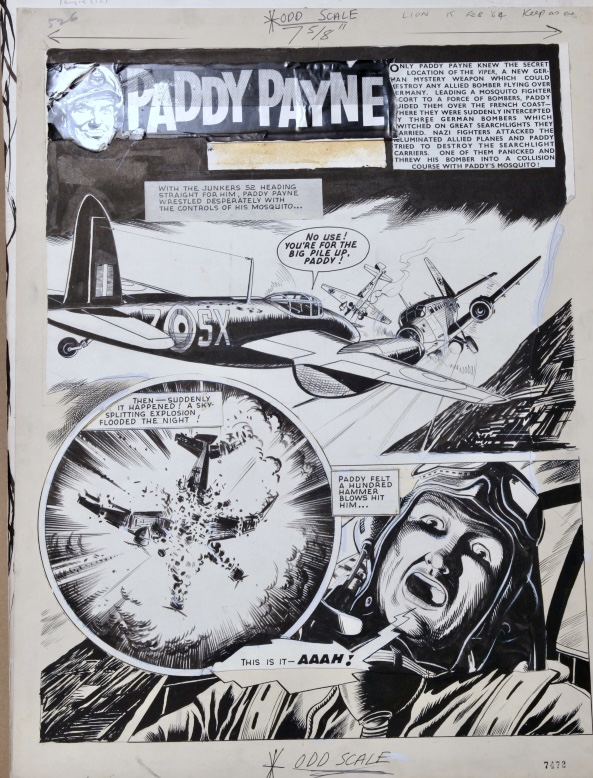

The English comics of those days were full of war hero’s real and make believe one I particular liked was of a RAF fighter pilot. My early comic reads were the Beano and the Dandy with Denis the Menace as one of the characters who got up to all sorts of mischief.

But when I was slightly older I read the Eagle and the Lion comics were the main characters being Dan Dare the spaceman and Paddy Payne the RAF fighter pilot. Paddy Payne stories were always on the front cover of the Lion.

This got my interested in model plastic aeroplanes planes made by Airfix

I was extremely knowledgable those days of all sorts of Second World War aircraft such as the Spitfire, Hawker Hunter and Lancaster bomber, Wellington Bomber And First World War aeroplanes such Sopworth Camel and Forker Triplane flown by the Red Baron the German fighter ace. All the aircraft models I constructed were from the Airfix range of plastic kit models.

Later I went on to building balsa wood aeroplanes using tissue and dope/ varnish for the wings and fuselage. They didn’t have a small engines but a propellor and a elastic band that ran down the fuselage.

Simple Rubber Band Powered Balsa Aeroplane

Wright Brothers first Manned Flight

I was always fascinated about the story of two brothers who were bicycle mechanics from Dayton Ohio in how they developed a heavy than air flying machine.

It’s wonderful story of real ingenuity and hard work, but more importantly in how they were able to scientifically develop their wing shape and size to give the correct lift to get them off the ground. Give the aircraft proper flight controls for tilt, roll and yaw which allowed the aircraft to go up and down and roll from side side and to turn left and right.

They developed ingenious ideas such as body shift to distort the wing to allow the aircraft to roll and turn which was also connected to a rudder to prevent counter yaw.

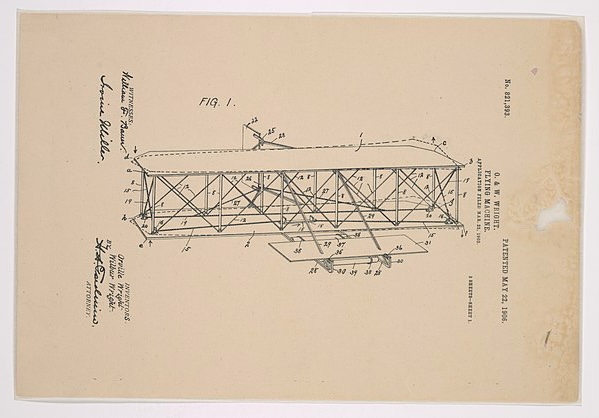

After modifying the glider’s rudder, the Wrights now had a true three-dimensional system of control. This three-axis control system was their single most important design breakthrough, and was the central aspect of the flying machine with patents they later obtained. In its final form, the 1902 Wright glider was the world’s first fully controllable glider.

Both brothers owed a small cycle manufacturing repair shop and they knew from riding a bike you have to learn to gain balance through forward motion by pedalling to give yourself and the bicycle propulsion by steering handlebars and front forks for lateral control.. That’s how they tackled aircraft flight control through balance and practice sequential development of the aircraft control mechanisms.

Hence the slow methodical processes before real powered controlled flight was achieved by them. . This took 4 years of pain taking experimental work and flight first with their tethered kites then manned glider flight to perfect basic controls then eventually engine powered man flight.

The third in a series of gliders leading up to their powered airplane, the 1902 glider was the Wright brothers’ most advanced yet. Reflecting their single, evolving design, it was again a biplane with a canard (forward) surface for pitch control and wing-warping for lateral control. But its longer, narrower wings, elliptical elevator, and vertical tail gave it a much more graceful, elegant appearance.

aileron ( roll longitudinal axis)

An aileron (French for “little wing” or “fin”) is a hinged flight control surface usually forming part of the trailing edge of each wing of a fixed-wing aircraft.

Ailerons are used in pairs to control the aircraft in roll (or movement around the aircraft’s longitudinal axis), which normally results in a change in flight path due to the tilting of the lift vector. Movement around this axis is called ‘rolling’ or ‘banking’.

Wright Flyer and the later, 1909-origin Blériot XI and Etrich Taube, lateral control was effected by twisting the outboard portion of the wing so as to increase or decrease lift by changing the angle of attack.

This had the disadvantages of stressing the structure, being heavy on the controls, and of risking stalling the side with the increased angle of attack during a maneuver. By 1916, most designers had abandoned wing warping in favor of ailerons. Researchers at NASA and elsewhere have been taking a second look at wing warping again, although under new names.

Rudder ( pitch, vertical axis)

At the rear of the 1903 Wright Flyer one finds a pair of rudders. The rudders are movable surfaces which are controlled by the pilot. This slide shows what happens when the pilot deflects the trailing edge of the rudders. How does changing the rudder angle affect the aircraft?

As described on the inclination effects slide, changing the angle of attack of a wing or airfoil changes the amount of lift generated by the foil. With increased downward deflection of the trailing edge, lift increases. The rudders are mounted so that they will produce forces from side to side, not up and down.

With greater rudder deflection to the right as viewed from the back of the aircraft, the force increases to the left (as shown in this slide). The force (lift) of the rudder is applied some distance from the aircraft center of gravity.

This creates a torque on the aircraft and the aircraft rotates about its center of gravity. If the pilot reverses the rudder deflection to the left, the aircraft will yaw in the opposite direction. We have chosen to base the deflections on a view from the back of the aircraft towards the nose, because that is the direction in which the pilot is looking

Elevator ( yaw Lateral axis )

At the front of all of the Wright brothers’ aircraft one finds the elevators. The elevators are a pair of movable wings which are controlled by the pilot.

Now remember the Wright brothers had no prior technical knowledge of the primary flight controls these they had to develop them by slow and systematic development through trail and error. First by tethered kite models than by manned gliders this was carried out over a number of years mainly at a place called Kitty hawk North Carolina.

Why there particularly?

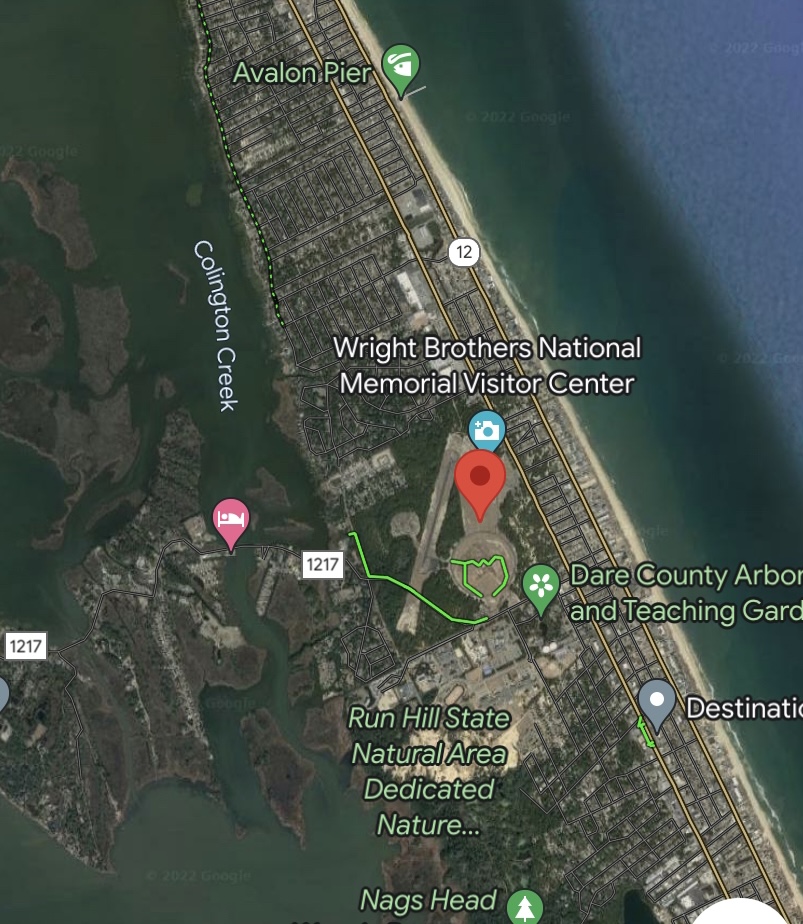

To test their gliders, the Wrights needed a site with wide-open spaces and strong, steady winds. Among the places that seemed promising was Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, a small fishing village on an isolated strip of beach on the mid-Atlantic coast.

Beyond the favorable conditions for gliding, the welcoming response to a letter Wilbur wrote to the local weather station settled the matter. William Tate, the best-educated resident of the little hamlet, enthusiastically endorsed Kitty Hawk as a fine place to conduct the experiments Wilbur described, and he offered to help in any way he could.

The Wright’s initially did not think that they would need a rudder on their aircraft since birds don’t need rudders. The 1900 and 1901 aircraft were designed without rudders. But during the glider flights of 1901, the brothers encountered flight conditions when the aircraft would suddenly spin out of control during maneuvers.

They included dual fixed rudders in the design of the 1902 aircraft to overcome this problem. The test flights of 1902 initially went better than in 1901, but in about one glide in 50 the glider would again spin out of control on recovering from a turn at low speed. Laying awake one night, Orville concluded that the rudders were acting as vertical wings in which turning generated an angle of attack and thus an unwanted force in the wrong direction.

His solution was to replace the twin fixed rudders with a single movable rudder. The next morning Wilbur agreed and offered the idea to tie the rudder deflection into the wing warping system.

Once done, the glider worked beautifully, keeping the nose of the aircraft pointed into the curved flight path. All subsequent Wright aircraft included dual, movable rudders.

The Wright’s used flat plate airfoils for their rudders and deflected the entire surface from side to side. On modern aircraft, the rudder is a separate piece attached to the vertical stabilizer.

The combination creates a symmetric airfoil and produces no lift when the rudder is aligned with the stabilizer. Forces to the left or right then depend on the deflection of the rudder. Modern fighter planes sometimes have two vertical stabilizers and rudders because of the need to control the plane with multiple, very powerful engines.

An arduous journey

Photo Kitty Hawk Google

The trip to Kitty Hawk was arduous, and weather proved unpredictable. Sudden squalls frequently blew in off the ocean, and the constantly shifting sand got into everything. Insects, especially mosquitoes, pestered them. Food was scarce, so the Wrights always brought their own provisions. Years later Orville remarked that the place was “like the Sahara, or what I imagine the Sahara to be.

Vacations nonetheless

Despite the hardships, Wilbur and Orville viewed their trips to Kitty Hawk as vacations. They enjoyed escaping the tedium of city life, grew fond of the Tates and other local folk they came to know, and found the chance to test their ideas in the field exhilarating.

The brothers always returned to Dayton feeling rejuvenated. Years later they would look back on their times at Kitty Hawk as some of the happiest of their lives.

The small tower at the back of the take off track was for a counter weight that was hoisted up to the top of the tower and released to give extra propulsion for the Wright Flyer to gain extra take off speed.

Sadly Wilber the driving force behind the Wright brothers died in 1912 of Typhoid fever brought on by the litigation over the wright flyer patents. He was depressed and run down over the stress involved with the legal issues making him susceptible to illness.

The patent: The concept of varying the angle presented to the air near the wingtips, by any suitable method, is central to the patent. The patent also describes the steerable rear vertical rudder and its innovative use in combination with wing-warping, enabling the airplane to make a coordinated turn, a technique that prevents hazardous adverse yaw, the problem Wilbur had when trying to turn the 1901 glider. Finally, the patent describes the forward elevator, used for ascending and descending.

Lawsuits begin

Attempting to circumvent the patent, Glenn Curtiss and other early aviators devised ailerons to emulate lateral control described in the patent and demonstrated by the Wrights in their public flights. Soon after the historic July 4, 1908, one-kilometer flight by Curtiss in the AEA June Bug, the Wrights warned him not to infringe their patent by profiting from flying or selling aircraft that used ailerons.

Orville wrote Curtiss, “Claim 14 of our patent no. 821,393, specifically covers the combination which we are informed you are using. If it is your desire to enter the exhibition business, we would be glad to take up the matter of a license to operate under our patent for that purpose.”

Curtiss was at the time a member of the Aerial Experiment Association (AEA), headed by Alexander Graham Bell, where in 1908 he had helped reinvent wingtip ailerons for their Aerodrome No. 2, known as the AEA White Wing.

Curtiss refused to pay license fees to the Wrights and sold an airplane equipped with ailerons to the Aeronautic Society of New York in 1909. The Wrights filed a lawsuit, beginning a years-long legal conflict. They also sued foreign aviators who flew at U.S. exhibitions, including the leading French aviator Louis Paulhan.

The Curtiss people derisively suggested that if someone jumped in the air and waved his arms, the Wrights would sue.

European companies which bought foreign patents the Wrights had received sued other manufacturers in their countries. Those lawsuits were only partly successful.

Despite a pro-Wright ruling in France, legal maneuvering dragged on until the patent expired in 1917. A German court ruled the patent invalid because of prior disclosure in speeches by Wilbur Wright in 1901, and Chanute in 1903. In the U.S. the Wrights made an agreement with the Aero Club of America to license airshows which the Club approved, freeing participating pilots from a legal threat. Promoters of approved shows paid fees to the Wrights.

The Wright brothers won their initial case against Curtiss in February 1913 when a judge ruled that ailerons were covered under the patent. The Curtiss company appealed the decision.

From 1910 until his death from typhoid fever in 1912, Wilbur took the leading role in the patent struggle, travelling incessantly to consult with lawyers and testify in what he felt was a moral cause, particularly against Curtiss, who was creating a large company to manufacture aircraft.

The Wrights’ preoccupation with the legal issue stifled their work on new designs, and by 1911 Wright airplanes were considered inferior to those of European makers. Indeed, aviation development in the U.S. was suppressed to such an extent that, when the U.S. entered World War I, no acceptable American-designed airplanes were available, and U.S. forces were compelled to use French machines.

Orville and Katharine Wright believed Curtiss was partly responsible for Wilbur’s premature death, which occurred in the wake of his exhausting travels and the stress of the legal battle. Not nice ending to all his and his brothers work Orville lived until 1948.

Victory and cooperation

In January 1914, a U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals upheld the verdict against the Curtiss company, which continued to avoid penalties through legal tactics. Orville apparently felt vindicated by the decision, and much to the frustration of company executives, he did not push vigorously for further legal action to ensure a manufacturing monopoly.

In fact, he was planning to sell the company and departed in 1915. In 1917, with World War I underway, the U.S. government pressured the industry to form a cross-licensing organization, the Manufacturers Aircraft Association, to which member companies paid a blanket fee for the use of aviation patents, including the original and subsequent Wright patents.

The “patent war” ended, although side issues lingered in the courts until the 1920s. In a twist of irony, the Wright Aeronautical Corporation (successor to the Wright-Martin Company), and the Curtiss Aeroplane company, merged in 1929 to form the Curtiss-Wright Corporation, which remains in business today producing high-tech components for the aerospace industry.

This reminds me of the RAF engineer who invented the jet engine Frank Whittle or Air Commodore Frank Whittle who was pilot and an engineer. It’s a fascinating story just as important as the Wright brothers story. In a way he was short changed over the jet engine development the British government gave away the jet engine design details to the US government at the beginning of world war 11.

Why they did that who knows? The US company General Electric took Frank whittles plans and developed their own jet engine. Because he was RAF engineer and serving officer the government in their wisdom gave away free all Frank Whittle jet design work and he was wasn’t financially rewarded for all his revolutionary design work.

Basically he didn’t get the financial recognition he deserved. Yes he got a knight hood and some money but he wasn’t recompensed for properly for his revolutionary design that completely changed aviation passenger industry for ever,

But that’s typical British story of commercial ineptitude! Frank Whittles own small business Power Jets was completely sidelined. Rolls Royce did the dirty on Frank Whittle and PowerJets. I’m sure he must have felt rather bitter about how shabbily he was treated by both the U.K. and the US governments. The U.K. stole his jet design plans and gave them away to other commercial companies for free!!

Profit and greed took over and Frank wasn’t a business man or entrepreneur with ruthless streak for money. Like Wilbur Wright it seriously effected his mental and physical health and he had a number of serious breakdowns and it took him many years to recover over all the commercial skulduggery with his unique jet design! Rather like the Wright brothers and their first aircraft patents and the legal situation that shorten Wilbur’s life.

In 1926 the Royal Aircraft Establishment under the guidance of Dr Alan Griffith begun theorising the development of the Gas Turbine for the powering of an aircraft.

The RAE authorised two experiments to be carried out to verify the theory and in 1929 a paper was publish that laid out the advantages of using a turbine to power an aircraft propeller. Due to the Great Depression, the Air Ministry was not willing to back the funding of the new engine and development stalled.

At the same time, a young RAF Cadet, the infamous Frank Whittle, was conducting experiments at the RAE and had begun formulating his own ideas for a jet engine. His idea differed from DR Griffiths and he proposed using the thrust of the exhaust to propel the aircraft.

His idea was also dismissed by the Air Ministry due to financial reasons. It was almost 7 years, under the guidance of Haynes Constant, before the RAE plucked up the courage to ask the Air Ministry to provide funding for the development of a Jet Engine. This time it was granted.

Finally these 3 brilliant engineers changed human travel for ever. The basic tenets for flight where formulated by the Wright brothers but aviation for mass transit was based upon the Frank Whittles invention of the jet engine.

This allowed aircraft to fly at 35,000 feet above the troposphere and the major atmospheric weather systems. This has allowed the mass transit of millions of people to fly all over the planet. To think this all happened within 40 years of the first flight of Wright Flyer was absolutely amazing.