I’ve been reading a book by Harold Gatty called “Nature Is Your Guide”.

Harold Gatty was interesting guy and was an Aussie from Tasmania. He like Francis Chichester was a wonderfully navigator and came to fame as the navigator for 1931 record breaking eight- day flight around the world with the pilot Wiley Post in the Winnie Mae aircraft.

The Winnie Mae was Lockheed Vega

High wing cantilevered monoplane with monocoque fuselage, fixed landing gear, ground adjustable propeller.

For his navigational achievement there was special act of the US congress and he was awarded Distinguished Flying Cross.

Harry Gatty honed his navigational skills not only using the sextant and compass but his observational skills as a natural navigator.

During World War 11 he produced a book for the US Army Airforce called the “raft book”. From that first book he developed and expanded on natural navigation in “Nature Is Your Guide”.

Harold states nature is a guide and gives you lots of guide-posts if you’re observant, however, today in modern western civilisation few of these guide posts are recognised. In course of his life he’d researched how early explorers relied on observing and interpreting the natural world around them. Which he uses the term the “Pathfinder”.

He taught navigation both marine and air to the United States Airforce. But he use to stress to all his students the importance of natural navigation.

When he did his record breaking flight as navigator when in the air he familiarised himself with the countryside below especially aspects that weren’t marked on conventional maps or charts.

Such as type of vegetation, crops, layout of farms, buildings, haystacks, fencing field boundaries. Wind direction by smoke of houses bending of the trees, type of livestock.

But it was also his interest in primitive people who had to use natural navigation to travel long distances. Such as the Polynesians, the Australian aboriginals and the American Indians using there five senses or sixth sense, which relates to time. Like the abo tracker down to his intelligence and reasoning and his bushcraft skills.

The most fascinating part as a sailor from his book was the colour of the sea, waves and swells and the habits of sea birds.

Deep sea sailing always makes me aware of the various animals I suddenly come across on my sailing journeys. Dolphins are always a joy to watch and I get a inner sense when they’re around.

But it’s the sea birds I find so special to watch especially the shearwaters in how they skim the surface of the sea and obtain lift from the waves. Their amazing gliding flight is awesome to watch. . Harold devotes one complete chapter to the Habits of sea birds which can indicate with some species you’re not far from land.

I noticed the Cory Shearwater like to sometimes follow me? May be the boat becomes focal point for them? Let’s look in little more details at the “Tubenoses” what’s a tubenose?

Adaptations for living on the sea-

Seabirds have evolved many ways of surviving the challenges of living a life intimately tied to the sea.

What adaptations help them find food and cope with excess salts? One group of birds, the Procellariiformes, evolved external tubular nasal passages, which describe their collective name “tubenoses.” Tubenoses include albatrosses, shearwaters, petrels, and storm-petrels.

All tubenoses have nostrils enclosed in a tube. The shearwaters, petrels (including the northernfulmar), and storm-petrels have onetube on top of the bill. Albatrosses have two tubes, one on each side of the bill. The tubular nostrils may help funnel scents, and tubenoses have an excellent sense of smell, which allows them to easily detect fish, squid, krill, and zooplantkton. (Some species also feed on carrion.)

Some species are nocturnal, and excellent olfaction is also important in finding nests on crowded nesting colonies.

Tubenoses drink seawater and have specially adapted nasal glands to cope with high salinity (approximately 3.5 percent). The nasal glands pump chloride and sodium ions out of the blood stream into secretions, which exit out of the nostrils and down along the grooves on the bill.

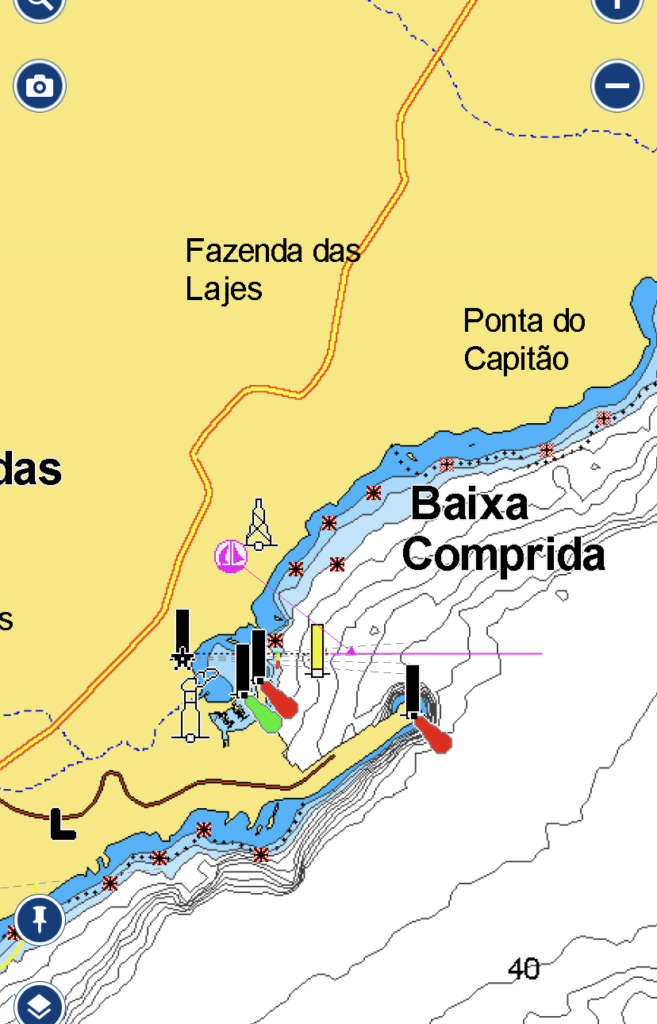

I remember I number of years ago when I was crossing the Atlantic west to east I had left Bermuda and arrived just as it was getting dark into the outer western islands of the Azores Flores into the small harbour anchorage of Lajes. When I anchored it was starting to go dark. There quite lot of steep cliff faces surrounding the anchorage.

I could hear this strange noise which sounded like a baby crying out. I thought what’s that noise strange?

I found out later what it was it was the Cory Shearwaters shouting out for their chicks on the cliff side.

Back to Harold and identifying land before you see it by sighting certain birds. Before I made landfall at Bermuda I remember a Bermudian white long tailed tropicbird trying to land on the top of the mast unfortunately for him to no avail?

Gannets normally don’t fly out further than the continental shelves which is up to 150/200nm from land. Gannets are large white sleek birds with yellowish head long beaks and narrowish wings but like pelican’s are superb divers. They have large wingspans of nearly 2 metres.

Gannets can dive from a height of 30 m (100 ft), achieving speeds of 100 km/h (60 mph) as they strike the water, enabling them to catch fish at a much greater depth than most airborne birds.

The gannet’s supposed capacity for eating large quantities of fish has led to “gannet” becoming a description of somebody with a voracious appetite.

If you’ve been on an ocean passage making landfall sight of gannet you know your not so far from land.

Frigate Bird.

I sailed to the Caribbean a few years ago in Barada my Nicholson 32 sail boat I went out to Barbuda from Antigua. I stayed onshore and with a friend we did a special trip to see a Frigate bird colony. Frigate birds are big black birds with a red chests and they are especially noisy birds in a colony. They have long wing spans and love to soar with a distinctive forked tail. They like to stay in the tropics and do migrate over large distances.

They are able to soar for weeks on wind currents and thermals. The frigatebirds spend most of the day in flight hunting for food, and roost on trees or cliffs at night when near land.

The 5000 bird colony in Barbuda they where nested inside the mangrove forest. Their main prey are fish and squid caught when chased to the water surface by large predators such as tuna.

Frigatebirds are referred to as kleptoparasites as they occasionally rob other seabirds for food, and are known to snatch seabird chicks from the nest. Seasonally monogamous, frigatebirds nest colonially.

A rough nest is constructed in low trees or on the ground on remote islands. A single egg is laid each breeding season. The duration of parental care is among the longest of any bird species; frigatebirds are only able to breed every other year.

When I left Antigua to sail to the British Virgin Islands I went into Nevis a small island below St Kitts. I anchored off Charles Town the capital of Nevis. I sat one morning watching the pelicans another tropical bird diving into the water from great height, I must say it was a wonder to watch them diving. Not only that they are great at low level flight and truly amazing gliders.

The brown pelican mainly feeds on fish, but occasionally eats amphibians, crustaceans, and the eggsand nestlings of birds. It nests in colonies in secluded areas, often on islands, vegetated land among sand dunes, thickets of shrubs and trees, and mangroves.

Females lay two or three oval, chalky white eggs. Incubation takes 28 to 30 days with both sexes sharing duties. The newly hatched chicks are pink, turning gray or black within 4 to 14 days. About 63 days are needed for chicks to fledge. Six to 9 weeks after hatching, the juveniles leave the nest, and gather into small groups known as pods.

On my special retirement Fred Olsen cruise around south America we sighted the wonderful iconic Albatrosses. The Albatross or as sailors use to call them the wandering Albatross are the biggest pelagic sea bird in the world. Like the shearwaters and the fulmars they are Tubenoses.

They frequent the south Atlantic and North Pacific oceans. Albatrosses are highly efficient in the air, using dynamic soaring and slope soaring to cover great distances with little exertion.

They feed on squid, fish, and krill by either scavenging, surface seizing, or diving. Albatrosses are colonial, nesting for the most part on remote oceanic islands, often with several species nesting together and like to

Pair bond between males and females form over several years, with the use of “ritualised dances”, and last for the life of the pair.

A breeding season can take over a year from laying to fledging, with a single egg laid in each breeding attempt.

A Laysan albatross, named Wisdom, on Midway Island is the oldest-known wild bird in the world; she was first banded in 1956 by Chandler Robbins.

Feathers of Birds are adaptation from the scales of reptiles. Feathers set birds apart from all other animals. Feathers are necessary for flight, insulation, and courtship displays.

Feathers are made out of keratin, the same protein found in hair and nails. Feathers have a central shaft. The smooth, unpigmented base, which extends under the skin into the feather follicle, is called the calamus.

Feathers with barbules and hooklets are termed “pennaceous,” and one can think of them as the feathers that would be used for a quill pen.

Feathers without barbules and hooklets, such as down feathers, are called “plumaceous” and have more the appearance of a plume. Some feathers have both pennaceous and plumaceous portions.

Some feathers have what are called afterfeathers, or hypopenae, at the base of the vane in an area called the distal umbilicus. These, really, are barbs without hooks, which help trap air and offer some insulation.

Feathers are not arranged haphazardly on the bird, but in major distinct tracts called pterylae. The featherless areas between the pterylae are called apteria.

Contour feathers

Contour feathers cover most of the surface of the bird, providing a smooth appearance. They protect the bird from sun, wind, rain, and injury. Often, these feathers are brightly colored and have different color patterns. Contour feathers are divided into flight feathers and those that cover the body.

Flight feathers

Flight feathers are the large feathers of the wing and tail. Flight feathers of the wing are collectively known as the remiges, and are separated into three groups.

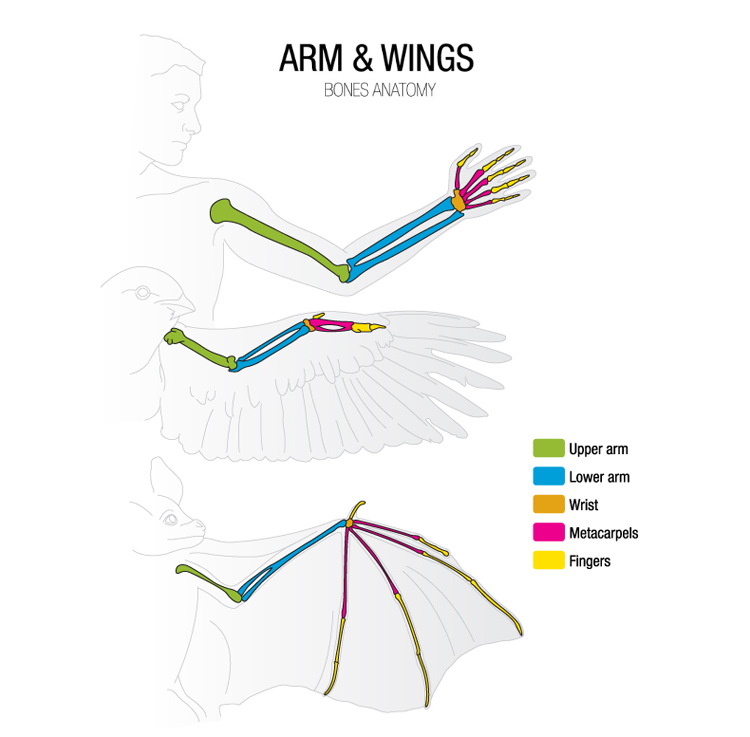

The primaries attach to the metacarpal (wrist) and phalangeal (finger) bones at the far end of the wing and are responsible for forward thrust. There are usually 10 primaries and they are numbered from the inside out.

The secondaries attach to the ulna, a bone in the middle of the wing, and are necessary to supply “lift.” They are also used in courtship displays. There are usually 10-14 secondaries and they are numbered from the outside in.

The flight feathers closest to the body are sometimes called tertiaries.

The tail feathers, called retrices, act as brakes and a rudder, controlling the orientation of the flight. Most birds have 12 tail feathers.

The bases of the flight feathers are covered with smaller contour feathers called coverts. There are several layers of coverts on the wing. Coverts also cover the ear.

Down feathers

Down feathers are small, soft, fluffy, and are found under the contour feathers. They are plumaceous, and have many non-interlocking barbs, lacking the barbules and hooklets seen in contour and flight feathers.

This makes it possible for them to trap air in an insulating layer next to the skin, protecting the bird from heat and cold. They are so efficient, humans use these feathers for insulation, too, in down jackets and comforters.

There are special types of downy feathers called powder down feathers. When the sheaths or barbs of these feathers disintegrate, they form a fine keratin powder, which the bird can spread over its feathers as a water-proofing agent.

The powder also assists in cleaning as the bird preens. The absence of powder down in birds such as cockatoos and African greys can be a sign of disease.

Filoplumes

Filoplumes are very fine, hair-like feathers, with a long shaft, and only a few barbs at their tips. They are located along all the pyterlae. Although their function is not well understood, they are thought to have a sensory function, possibly adjusting the position of the flight feathers in response to air pressure

Semiplumes

Semiplumes provide form, aerodynamics, and insulation. They also play a role in courtship displays. They have a large rachis, but loose (plumaceous) vanes. They may occur along with contour feathers or in separate pterylae.

Bristle feathers

Bristle feathers have a stiff rachis with only a few barbs at the base. They are usually found on the head (around the eyelids, nares, and mouth). They are thought to have both a sensory and protective function.

Feather growth

Like hair, feathers develop in a specialized area in the skin called a follicle. As a new feather develops, it has an artery and vein that extends up through the shaft and nourishes the feather.

A feather at this stage is called a blood feather. Due to the color of the blood supply, the shaft of a blood feather will appear dark, whereas the shaft of an older, mature feather will be white.

A blood feather has a larger quill (calamus) than a mature feather. A blood feather starts out with a waxy keratin sheath that protects it while it grows. When the feather is mature, the blood supply will recede and the waxy sheath will be removed by the

Bird Anatomy

Birds are warm blooded with a normal body temperature of around 40°C, several degrees warmer than most mammals. They also have two eyes and two ears, though these are not normally visible.

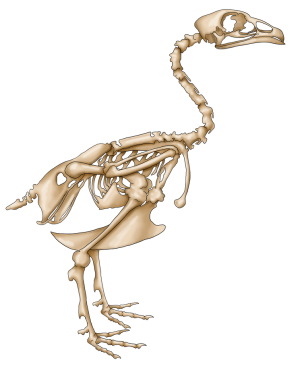

Most birds have little or no sense of smell. Birds have also had to evolve a compact body shape in order to facilitate flying. All the major skeletal differences between birds and their reptilian ancestors are a response to the requirements for flight.

All birds have the same basic plan.

Though different life styles have meant that they have evolved different variations on the central theme.

Flight means lifting the birds weight, so the first major consideration is reduction in weight. The lighter you are, the easier it is to fly. The main ways birds have lost weight is through the loss of teeth and the large jaw bones needed to support teeth. Plus the loss of nearly all the tail and a reduction of the skull.

Though a bird’s major limb bones are hollow, with internal struts for support – this makes them stronger not lighter. A bird’s leg bones for example, are often heavier than those of a similar sized mammal or reptile.

The flapping of wings to achieve flight requires huge muscles… and these muscles need to be solidly attached to the bird’s skeleton. They also to generate tremendous stresses in the skeleton when working.

A bird gets around the first problem by having a greatly enlarged sternum, sometimes called a keel or carina – which we call the breast plate.

The rigidity has been achieved by fusing groups of vertebrae, fusing the two collar bones to make what we call the ‘wishbone’. And by the addition of special lateral (sideways) growths on the ribs – which rest against the next rib back and thus strengthen the whole ribcage.

These extensions are called uncinate processes .

A bird’s thorax is squat and compact in comparison with most other vertebrates. This brings the operation of both the legs and the wings closer to the centre of gravity, allowing them to work more efficiently.

This also gives a bird a better balance, important in both flight and bipedal (two legged) locomotion.

To keep their centre of balance when walking, birds have evolved to have their equivalent of our thigh held permanently close to the body.

The leg does not start to extend out from the body until after the knee joint – which is never seen.

The backward bending leg joint – that you see in bird’s legs when they are walking – is the equivalent of our ankle.

A bird’s foot is the equivalent of the tips of our toes. Thus the part of a bird’s leg that looks like its shin is actually the equivalent of the arch of our foot.

Birds Feet

The stresses involved in landing and taking off, in running and in hunting – mean that a variety of birds have relatively heavy and strong leg bones.

The fundamental bones of a bird’s leg are the femur, fibula, tibiotarsuss and tarsometatarsus. These are also called the femur, tibia and tarsus respectively, in an external view of a bird’s anatomy.

Most birds have four toes.

The first points backwards in most species – and consists of a small metatarsal and one phalanx (toe bone).

The second, third and fourth digits (or toes) are counted from the inside of the foot out… and have 2, 3 and 4 phalanges respectively. The fifth toe is lost completely, except in some birds where it has become a defensive spur – such as the chicken.

The foot is a very important appendage for a bird, being the only source of support when standing, walking and running on a variety of surfaces.

A bird’s feet are also its means of propulsion in aquatic species. A major weapon in many predatory species. And for some birds, their equivalent of a hand – functioning to grasp and hold objects the bird wishes to manipulate, mostly during feeding.

The size and shape of the claws, the way the toes are arranged – as well as the length of the toes and the degree of webbing – are all dependent on what a bird uses its feet for and where it lives.

Like a bird’s bill or beak, its feet reveal a lot about its lifestyle. Many birds have three toes forwards and one back. Others have two forward and two back.

Ducks, Geese and Swans all have medium length toes joined, together by a web of skin to make an excellent paddle for rowing themselves through the water.

They spread the toes on the back stroke, to maximise the push. Then hold their toes together on the forward stroke, in order to reduce resistance.

Finally never underestimate the power of nature and birds are the most awesome flying machines.